*Spoiler Alert: detailed film analysis below*

Laputa: Castle in the Sky, or 天空の城ラピュタ or Tenkū no Shiro Rapyuta, was Studio Ghibli’s first official film, released in 1986. It is unique because it was distributed under various names, with varied English dubs, and even a secondary score. The film solidified much of what the world would come to expect from Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki.

Castle in the Sky, as the name is often shortened, centers around the legendary floating island called Laputa. When Sheeta, a young girl, falls from an airship and is saved by her mystical amulet, young Pazu discovers her floating toward the main mine of the town where he works. After they meet, a daring and mythical adventure ensues, with dirigible airships, sky pirates and their flaptors, the military led by a greedy egotist, robots, magic elements, and beautiful animated environments.

The film was treated to no less than three two English dubs, each from separate distributors, which remains the cause of some controversy among die-hard fans. In 1989, Magnum Video Tape & Dubbing produced an English dub for international Japan Airlines; this version was briefly screened in the US by Streamline Pictures, whose head-man was disappointed by the dub’s “clumsy” results. Streamline still distributed the dub was allowed to develop their own dub, which was released on its first Japanese DVDs, along with the Streamline-dubbed My Neighbor Totoro and The Castle of Cagliostro. However, the English dub most familiar to American audiences is the Disney dub. Unfortunately, while entertaining and relatively accurate, the Disney English dub remains a source of frustration among fans for reasons we’ll return to shortly.

*Edit: Streamline did not, in fact, develop their own dub for “Castle in the Sky,” only distributed the Magnum dub, reluctantly. Thank you to our readers for the correction.*

In researching for this article, as I do for every review, I came upon a New York Times review, dated August 1989, that was not only poorly written but entirely missed the point of the film. I realized that, despite previous Miyazaki films existing, the American critics of 1989 were still unsure what to make of these unusual films. The fundamental misunderstanding of animation, which many Studio Ghibli films confront and oppose, is the assumption that these stories are simply “for children,” which is derogatory to both the films and children. The stories are beautiful and true works of art that could be transposed to live-action “for adults” if desired, but the chosen medium was animation. And that medium does not inherently provide a genre.

The Disney dub unfortunately prolongs that misunderstanding. Produced in 1998 and distributed in 2003, Disney made several changes to the first Studio Ghibli film, to better suit American audiences: more humor and one-liners, approximately 30 more minutes of score from Joe Hisaishi, a change in Sheeta’s significance to the pirate crew wherein she oddly became a romantic interest instead of a mother figure, and – something hardcore fans may never forgive – a slight rewriting of Sheeta’s final speech. The new score covered any uncomfortable silences, something American audiences always seem uncomfortable with, and the new humor softened the already comedic characters of the Dola Gang. But, thanks to the Dola Gang, the film’s action also picked up.

Miyazaki action sequences, even when violent, are incredibly artistic and, in the case of the Dola Gang, often displays of comedy. As antagonists go, Castle in the Sky set the stage for a common characteristic: the grey of the moral compass. Miyazaki antagonists are hardly strictly evil, but instead inhabit the spectrum, with their own goals, desires, and moral codes that will sometimes align with the protagonists. For example, the Dola Gang turn out alright in the end, which is more than can be said for the military and government portrayed. It’s important to remember that the setting is an alternate Earth, with no familiar geographical settings or specifically called out governments, and with a date somewhere between 1868 and 1900, as Pazu’s father captured Laputa’s photo in July of 1868.

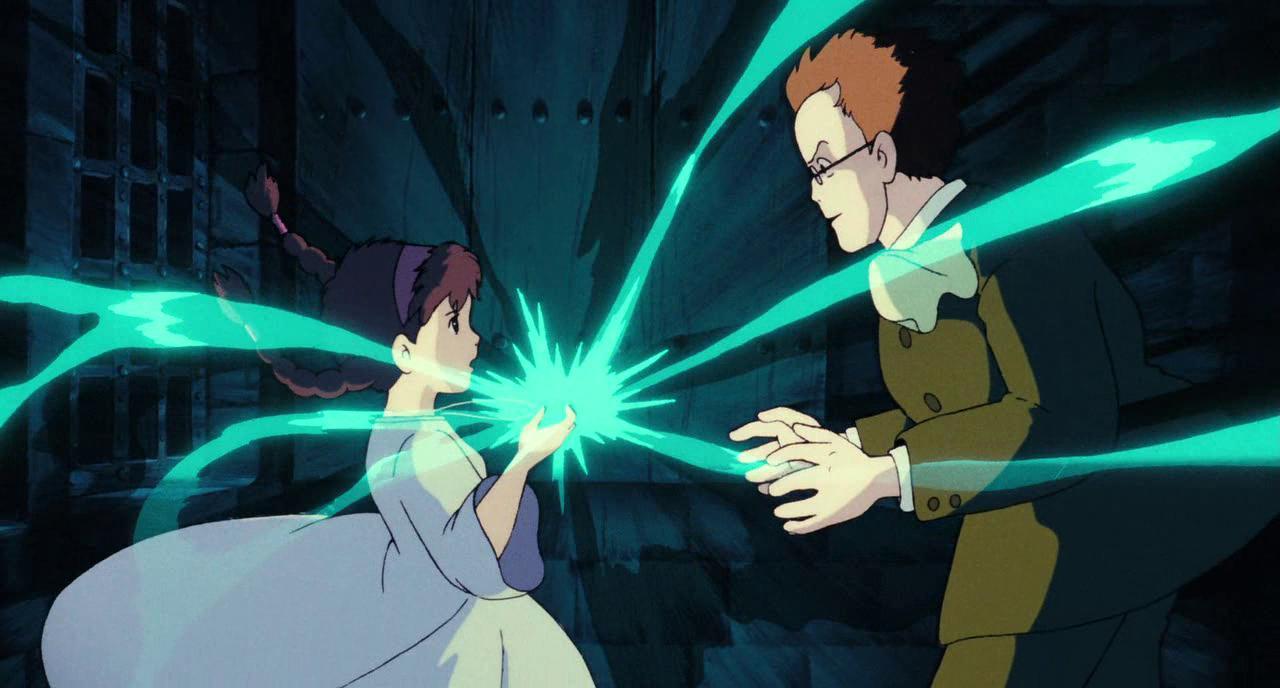

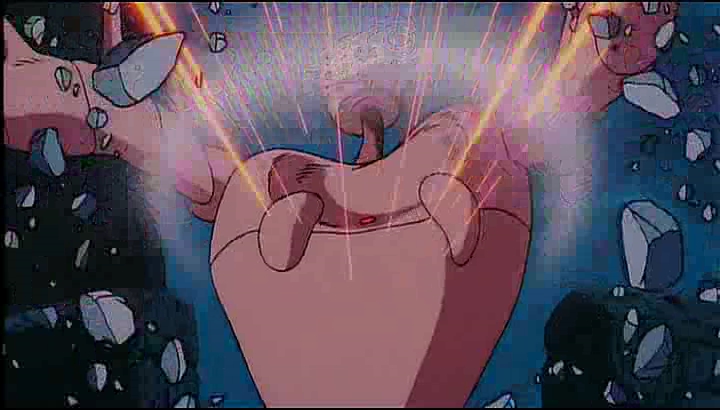

Castle in the Sky also stands as one of those rare films that successfully blends magic and science. The magical properties produced by Sheeta’s necklace are, in fact, born from an element called Aetherium (or Volucite, in non-Disney releases), something intrinsic within the Earth that man once knew how to mine. The opening credits of the film, if one pays attention closely, tells the story of how this element was mined, collected, and eventually used to engineer great strides of technology, such as floating cities and highly protective robots; however, it also fostered weapons, war, and greed. The power produced by Sheeta’s crystal appears as magic, but it’s intriguing to consider it as a scientific reaction.

The initial reaction, of course, is to wake a damaged robot, intent on reaching and protecting Sheeta, though she’s not aware of it. In addition to commentary on weapons, fear, and violence, this sequence also reminds the audience of the reality of Studio Ghibli films. Despite the family-friendliness of some of his films (Totoro comes to mind), it’s an important truth that these are not films to plop your children in front of, expecting a neatly and happily wrapped little moral at the end; but that’s not to say you shouldn’t.

These films offer a reflection of reality that is infinitely essential for children, developing critical thinking skills, empathy, and the ability to form their own opinions. Though peppered with violence, abuse, and corruption, Castle in the Sky tells a significant story in a pleasing and entertaining way, almost as an epic legend thanks to the attention to detail Miyazaki gives his world-building.

A common and widely accepted fact of Miyazaki’s films is how easily and willingly he combines cultural aesthetics in his world-building. While the name Laputa comes from Gulliver’s Travels, the floating island is also connected to Biblical and Hindu legend in the course of the film, providing it even more of a mythological legacy.

Despite the ancient nature of the story, the most important aesthetic derived from Castle in the Sky, and Miyazaki films usually, is the Victorian and almost Steampunk ambiance, here featured prominently on the pirates’ airship. The castle itself features medieval architecture, the village surrounding the military fortress is fairly Gothic, and the mining-town is distinctly Welsh in architecture, clothing, and even vehicles. The Welsh tone was inspired by Miyazaki’s real-life visit to Wales in 1984, where he witnessed the miners’ strike firsthand; it was the beginning of Castle in the Sky, as Miyazaki strove to “reflect the strength of those communities.”

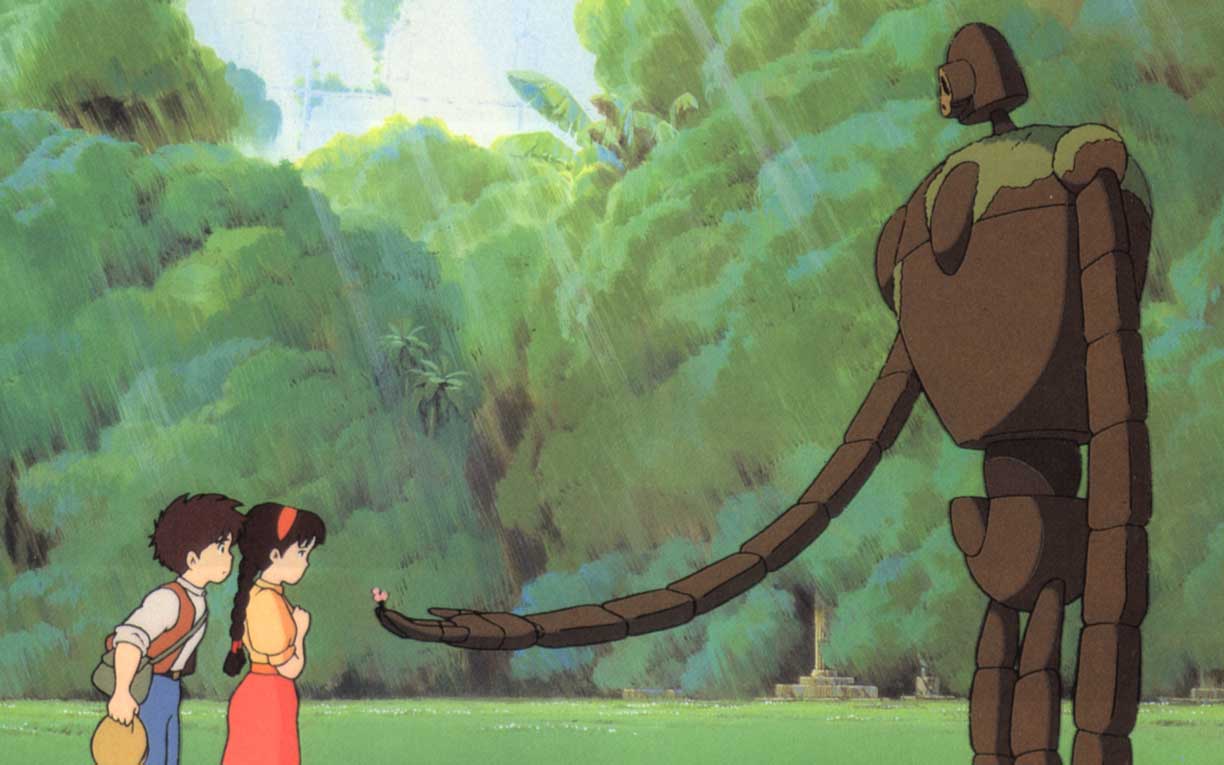

Miyazaki’s strong communities and worlds are always well-formed, three-dimensional, and unapologetically immersive. In addition to thrusting his new world upon an unsuspecting audience, Castle in the Sky also cemented several themes among the forming standards of a Studio Ghibli film. Like the new technological creations or the government corruption, Miyazaki is also known for including commentaries on war and on environmentalism. Here, he displays the military as greedy, over-bloated, and even stupid, but that unkind portrayal is more of a backdrop for the environmental stance Miyazaki takes. For Miyazaki, it is not man versus nature or technology versus nature. Rather, Castle in the Sky places the human race where they should be – as just one of many species inhabiting nature.

If any parents are still looking for that neatly wrapped moral, the closest they will find is Miyazaki’s view that nature will remain the dominant force and we, as one simple species, must come to respect and cooperate with that force. The Laputa that Pazu and Sheeta find is not simply a crumbling wreck nor is it entirely devoid of human legacy; the single remaining robot has embraced the nature enveloping the island, protecting birds’ nests and gingerly holding flowers while still remembering the people who once lived there. Here, Miyazaki introduces his environmental beliefs to the world, with gorgeous art, wonderful scenes, and sincere ideas.

And it is here that the Disney dub fails. Those familiar with the dubs usually have several points of frustration with the Disney version. On the whole, the Disney dub maintains accuracy, rewording where necessary to match lip movement. However, it is in the fundamental misunderstanding of the animation medium, wherein parents expect a neat little moral for their children, that strikes down the Disney dub when they rewrite Sheeta’s final speech.

From original subtitles, paraphrased:

There’s a song in my valley: “Put down your roots in the soil. Live together with the wind. Pass the winter with the seeds, sing in the spring with the birds.” Your weapons may be powerful. Your sad robots may be many. But you cannot survive apart from the Earth.

This, of course, maintains Miyazaki’s environmental argument and the basic point of the film. The following, however, does not:

There is a song from my home in the valley of Gondoa that explains everything. It says, “Take root in the ground, live in harmony with the wind. Plant your seeds in winter, and rejoice with the birds in the coming of spring.” No matter how many weapons you have, no matter how great your technology might be, the world cannot live without love.

That final sentence is a diversion from the rest of her powerful, beautiful monologue, giving her instead only weakness and cliche in a sad display of the American ideals of animation. There is the nice little moral and, in giving that, Disney disrupts one of the most powerful truths of Studio Ghibli films: the world’s lessons are not simple nor straightforward nor direct nor wrapped up in a nice little sentence at the end of the day. Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki’s films depend on the decisions and interpretations of their protagonists, just as your life depends on your decisions and your personal interpretations.

Laputa: Castle in the Sky enjoys a 95% Fresh rating on RottenTomatoes, and an 8.1 out of 10 on IMDB.

What do you think of Studio Ghibli’s first film? How do you feel about dubbing issues in Studio Ghibli films?

Edited by: Hannah Wilkes