*Disclaimer: Spoilers ahead.*

The tale of a mustang in the days of the Old West, when great herds of buffalo still roamed the plains and the railroad was growing, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron faces westward expansion from the perspective of a wild horse. A steady story, with strong animation and enveloping music, this film takes on animal characters and plot without excessive anthropomorphism, dumbing down, or unnecessary comic relief.

Released on the 24th of May, 2002, Spirit was written by John Fusco (Hidalgo), directed by Kelly Asbury (the Shrek franchise) and Lorna Cook, and starred Matt Damon as Spirit’s narrative voice, James Cromwell as the Colonel, and Daniel Studi as Little Creek.

The Story

John Fusco was hired to write a screenplay based on an idea from Jeffrey Katzenberg; Fusco took the project very seriously. First, he wrote a novel for Spirit‘s story, and then adapted his own work into a screenplay for the film. In a way, that explains the film’s flow, built atop fully detailed prose rather than starting from storyboards and screenplay.

Although written with the added appeal of minimal dialogue, Spirit’s own narrative voiceover remains a constant through the film, initially welcome but sometimes unnecessary. The story is simple enough and visual enough to keep the viewer informed and intrigued. The viewer watches Spirit travel from his own gorgeous homeland to a military outpost to a Lakota village to the expanding railroad construction. It’s a grand Western adventure in every sense, except that there’s nary a cowboy in sight.

Instead, the film is a story of freedom, and not just gaining that freedom. Making a point sometimes forgotten, everything and everyone is born free. Spirit’s story is the struggle to regain that freedom, whether from the branding and constrictive harnesses of the military or the open companionship and family offered by the Lakota boy, Little Creek. There is freedom in choosing one’s place of belonging, just as Rain chooses her home with her loyalty to Little Creek; but for some, like Spirit, the only freedom is true freedom, and Little Creek recognizes it before anyone else does, giving the stallion his name, “Spirit… Who Could Not Be Broken.” A more appropriate name might be Spirit Who Could Not Be Owned, as this deep dive into a horse’s point of view gives him an undeniable realism, something that, for lack of a better phrase, makes him all the more human.

The Animation

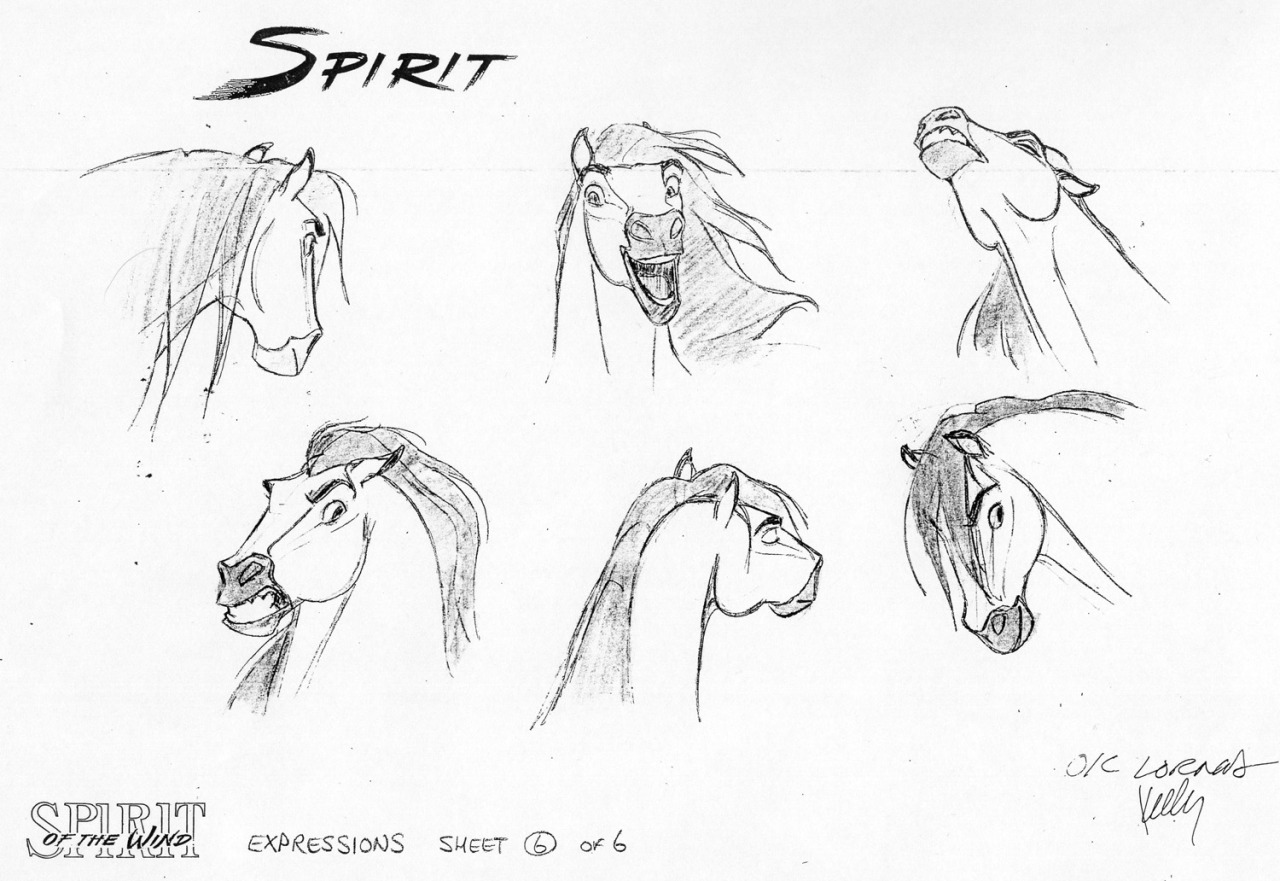

The production team was given all the inspiration possible to build the onscreen storytelling details that even beginning animation fans can appreciate. A horse model, purchased by the studio, was brought in for animators to study, learning all the small movements and sounds and ways that horses communicate. In addition to recording real horse hooves in action and true horse voices, the team took a scenic tour through the classic Old West of the United States, what would become Spirit’s homeland on screen.

Created over four years, the film uses ‘tradigital animation,’ or a mix of traditional hand-draw animation and computer animation, which can be noted particularly in scenes with transportation, such as the railroad scenes that feature a train engine.

The animation has aged well, despite some glaring moments and some issues with lack of detail in close-ups, but is overall not an aesthetic standout. Even with incredible emotional detail among character design, almost no scene in particular is visually memorable. Unfortunately, this makes for a somewhat resigned dependence on the other strengths of the film.

The Music

In addition to strong story, the film boasts a strong score, composed by none other than the great Hans Zimmer. With wide open crescendos, thrusting spirits to the sky, and deep emotional pulls, creating tears and smiles, Zimmer gives Spirit an intense musical beauty. From the first opening notes, the viewer is pulled in, watching intently and feeling a sense of their own freedom.

The soundtrack, by Bryan Adams, is still an excellent fit, achieving Western vibes without going nauseatingly country, and often hitting close to home with poignant and deep lyrics. And, even though the songs fit with the story’s flow, even facilitating it at some points, the soundtrack is not memorable. Worthy of playlists and personal motivation mixes? Yes. But attaining that memorable sing-a-long value a la Disney? Not quite. “You Can’t Take Me” and “Get Off of My Back” are standouts for their more upbeat and catchy melodies, standing against softer but still eloquent songs like “Here I Am” or “Sound the Bugle.” Listening to these songs, in or out of the film, they each resonate emotionally, but being able to sing them offhand is unlikely.

The Film

Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron is a powerful film in the moment, tugging the heartstrings easily if one is watching with undivided attention. Yet, the film does not quite reach that goal of impressioned excellence, as there is little takeaway after the fact. The credits roll, maybe a few satisfied sighs, some final dabs of tissue and blowing noses, some remarks of “Wasn’t that a good one?”, and then there is a general shuffle back to the flow of everyday life.

Spirit is not a life-changing film; it is, however, one of the few animated films to embrace deeper topics with little comfort padding. But, after all that, when that final scene closes, the viewer remembers the Old West, a horse, and a successful fight for freedom.

Edited by: Morgan Stradling