If you read this website you know the name Walt Disney. But, though it may seem like a travesty, many people don’t. That being said, even if you know the term “Disney” is rooted in the legacy of a man rather than the dominance of a corporate synergy machine, how well do you really know that man? Who was he? What was he like? What fueled his passion? These are the questions the new PBS documentary American Experience: Walt Disney explores. The exquisite journey back in time airs in two parts on September 14 and 15 at 9:00pm EST. I recently had the privilege of chatting with Sarah Colt, the film’s director. In this interview, we talk Walt, the documentary’s origins, and the true necessity of why this movie needed to be made.

Sarah Colt: Hi!

Blake Taylor: Hey! Thank you so much for talking with us. I know a lot of our readers and listeners are really looking forward to this documentary.

SC: Oh, good. That’s exciting. I was just looking at your site, which I was looking at for earlier projects, but I hadn’t looked at it in a while. It’s great.

BT: Well, thank you very much. That means a lot to us. We’ll just dive right into these questions.

SC: Sure.

BT: Perfect. So you’ve directed a few American Experience episodes before. How did you first become involved with this particular project, or how did the project even come to be about identifying Walt Disney as somebody who the program would want to spotlight?

SC: Well, I have to say, I know that my executive producer at American Experience, Mark Samels, had his eye on Walt Disney for many years. PBS has another series, American Masters, and for a while there, it looked like American Masters was going to get to do Walt Disney. It turned out that they had sort of shelved it for the time being, and Mark Samels decided that he would try to see if the Disney Company would be open to the project. As you might imagine, this project is really only possible with their agreement. You can’t do a film about Walt Disney without the company saying that it’s okay. They need to let you get into the Archives and allowed into the collection and also allow us to do it at a level that isn’t so astronomical that we can’t afford it, since we’re PBS. So really the critical juncture for this project going forward was, “Could we get the Disney Company to agree?”

Mark approached me about the project. I had done a film about Henry Ford, and that project actually made me start thinking about Walt Disney as a topic for the first time because the biographer for Henry Ford also did a very good book about Walt Disney. His name is Steven Watts. So I started thinking about Walt Disney because of that. Anyway, when Mark approached me, I was thrilled. I mean, can you imagine a better topic? It’s a very exciting topic for a documentary filmmaker, and I really did enjoy making biographies, so I thought it was intriguing. Then, when we were able to meet with the Disney Company and they were actually open to the idea of letting us into their collection and also understood that they couldn’t have any editorial control over the project, that they would agree to that. Normally the Disney Company wants to see their projects before it’s published or broadcast, and we just said, “That’s not possible for PBS. We can’t do that.” So, as soon as they agreed, we were full steam ahead.

American Experience does small stories and big stories. They do presidents and they also do smaller stories. Walt Disney, in terms of cultural impact… it’s hard to imagine anyone with as much impact on American culture as Walt Disney. He was clearly an important person to examine.

BT: Right. You touched on having the blessing of the Disney Company, and I think that’s something that brings a lot of authenticity to the documentary. As you go through Walt Disney’s life, you’re able to refer back to actual clips and photographs that are obviously from films or productions that Disney did throughout his life. What was the working relationship between the filmmaking team and the Walt Disney Company? Or did it just end, like you were saying, after that first initial meeting?

SC: Oh, no. I mean, that initial meeting… Becky Cline, who is the head of the Archives, was in that meeting that I had, and Mark Samels had had a couple of meetings with her previous to that. But Becky was really crucial to the project from the beginning. She introduced me and my team to all the relevant staff people on her head staff and then also in the footage library, basically. So we worked very closely with them throughout the project, and, you can imagine, the research started going from the beginning and kept going right up through the end of the project. We were working with them all the way through. They were extremely helpful. It’s a tough situation to get their company, and coming in with a PBS team isn’t really their… they have a lot of other priorities, so they had to make time for us, which we really appreciated. I also got to work very closely with their head of licensing, and, as you can imagine, it was a big licensing deal that had to be put together.

BT: With having four hours to flesh out the whole story of someone as iconic as Walt Disney, how do you even begin to decide, “All right. Four hours is a lot of time, but where do we focus our attention?” What kind of challenges did your team face in presenting this full story in one single documentary?

SC: Well, we initially planned it as a two-hour project, and then when we worked on it, I worked with a writer. When we wrote it out as a script at two hours, if you translated what we wrote into a television series, it was really more like three/three and a half. When we came to my executive producer, Mark Samels, he read it and said, “We need to make this longer. We’re not going to be able to do it at two hours—that’s going to cut out so much good stuff.” So we went from two hours to four hours, which now I’m very happy we did. At the time, I was nervous, like, “Oh, God.” I think it’s important as a filmmaker to not go on and on and on. You really need to find your story, but I do think it carries at four hours. Certainly we could have gone on much longer than four hours, actually. There are a lot of things that aren’t in there, but I think that it works very well at four hours.

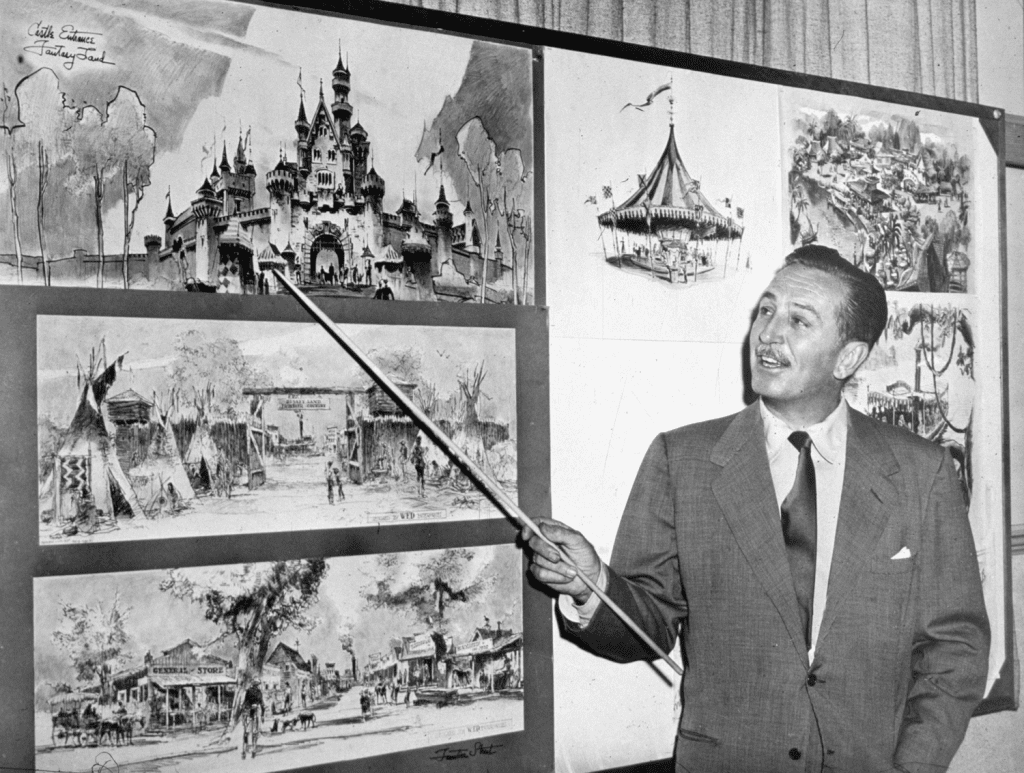

My goal with the film was to really understand Disney as a person. The question throughout in terms of creating the narrative arc and making you’re always sticking close to Disney himself was, “What was Disney doing? What was he passionate about in that moment?” The Disney Company obviously grew and the studio was doing a tremendous amount. Disney himself was incredibly productive, but as you get into Night Two [of the documentary’s two-night broadcast], what’s at the front of his mind becomes the narrative arc. There’s a lot of films we don’t mention and a lot of films that people may be disappointed that we don’t talk about. 101 Dalmatians, The Jungle Book, and some of his live-action films we don’t go into. That was because those films weren’t… not that he wasn’t involved, but they just weren’t the passionate projects for him that Disneyland became. After Disneyland opened, Disneyland really was his focus, and then he started putting his focus toward EPCOT. That was how we tracked the narrative.

Right from the beginning, the strike was clearly a critical turning point, and so there was always going to be a break there, whether at two hours or four hours. The strike really was kind of a turning point in his life. I’m always interested, when you’re thinking about biographies: What are your transformative moments for your character? And the strike is really a transformative moment for Disney in many ways, so we end Night One with the strike and we open Night Two with the strike because it’s such an important moment.

BT: And something that this production is able to do that a lot of productions in the past haven’t done is really give a full scope of the entire life as opposed to just zooming in on one specific aspect. You get to see how all the things connect and get a full, complete picture. You mentioned the word “character,” and the film goes into the distinct separation of Walt Disney as a real person, and then Walt Disney as an image just as fictional as one of his own animated characters. How did you manage the balancing act of showing both of those qualities fairly and accurately?

SC: Well, it was really interesting because I saw a lot about it and I asked all the people I interviewed about what he was like: How did he compare to his television persona? When you think about Disney in the ’20s and the ’30s—you see it in the footage—he’s so different. He’s much younger, he’s much skinnier, but he also presents differently. He’s a younger man; he’s even kind of flashy-clothed. He seems more extroverted and out there in that way. By the time we’re in the ’50s or ’60s, he’s an older man, you never see him in anything but a suit, he’s gained quite a lot of weight, he’s aged. The later Disney is the Disney that people… if they even know who Disney is, that’s who they know. They know the man on television, the Uncle Walt character.

The big question for me was, “Is that a true representation of who he is, or is that some sort of made-up character?” The way I felt was that Disney was an aspect of Disney, but clearly and very importantly not the full man. As Richard Schickel said in the film, nobody does what Disney did as an affable, friendly Uncle Walt. That just isn’t possible if he was a real mover-shaker. He did things that are amazingly bold and took incredible confidence and incredible drive. You just don’t get those things from somebody who’s just a happy-go-lucky kind of guy. I think it’s true that in a way he was both those things at once, and in some ways I don’t necessarily think those are contradictory. Lots of people are full of complexity. Some of our most talented and successful people are very complex. Disney is complex. That was the challenge and hopefully the success of the film is that, by the end, you get a sense of this very layered human being. That he’s not all one thing or all the other. But I don’t think he’s a phony when he’s Uncle Walt. He’s incredibly connected to children, and he loves children. He takes children very seriously in a way that a lot of adults especially then and certainly now don’t. He understood that children are thinking, thoughtful human beings, they’re just immature. They’re just young. I think that really translated and that’s part of his appeal.

BT: That’s a great answer. All right, last question: What do you hope the viewer takes away from this full film experience?

SC: Well, you know, I think it’s kind of connected to what I was just saying. Disney is this iconic legend, and there are young people today who don’t even know Walt Disney was a person. They just know it as a brand. They know that it’s about Disney World or Mickey Mouse or their favorite Disney film or Disney Channel, watching Disney on TV. They don’t really know… I mean even the name “Disney” isn’t a common name. It’s not like Ford or something where you know that’s connected to a human. So I think a lot of people have no idea it’s a person, or if they know it’s a person, there are so many myths and so much that surrounds him because of his success that people don’t know that he’s real. Hopefully the film will make him human. Disney evokes a lot of passion. Either people love Disney or they hate Disney. There’s a portion of the population that thinks Disney ruined American culture, and all that kind of stuff. For everyone in that sector of people, I think the film will hopefully make them understand his contributions and make them understand who he was as a person—that there was a real person behind all this output that we now live with still today. That’s the key. That’s our hope that the film achieves.

BT: That’s good. Well, thank you so much, Sarah. I know that all of our readers and listeners are looking forward to seeing the film when it airs.

SC: Oh, good. Good.

BT: Thank you so much for your time.

SC: Oh, yeah. Thanks so much.

American Experience: Walt Disney airs September 14-15 at 9:00pm EST on PBS.

After hearing Sarah’s insight, what are you most looking forward to in this documentary? What do you hope to glean?

Edited by: Hannah Wilkes